Photo Credit: Greg Lavaty

Whooping Cranes – Wintering in Texas

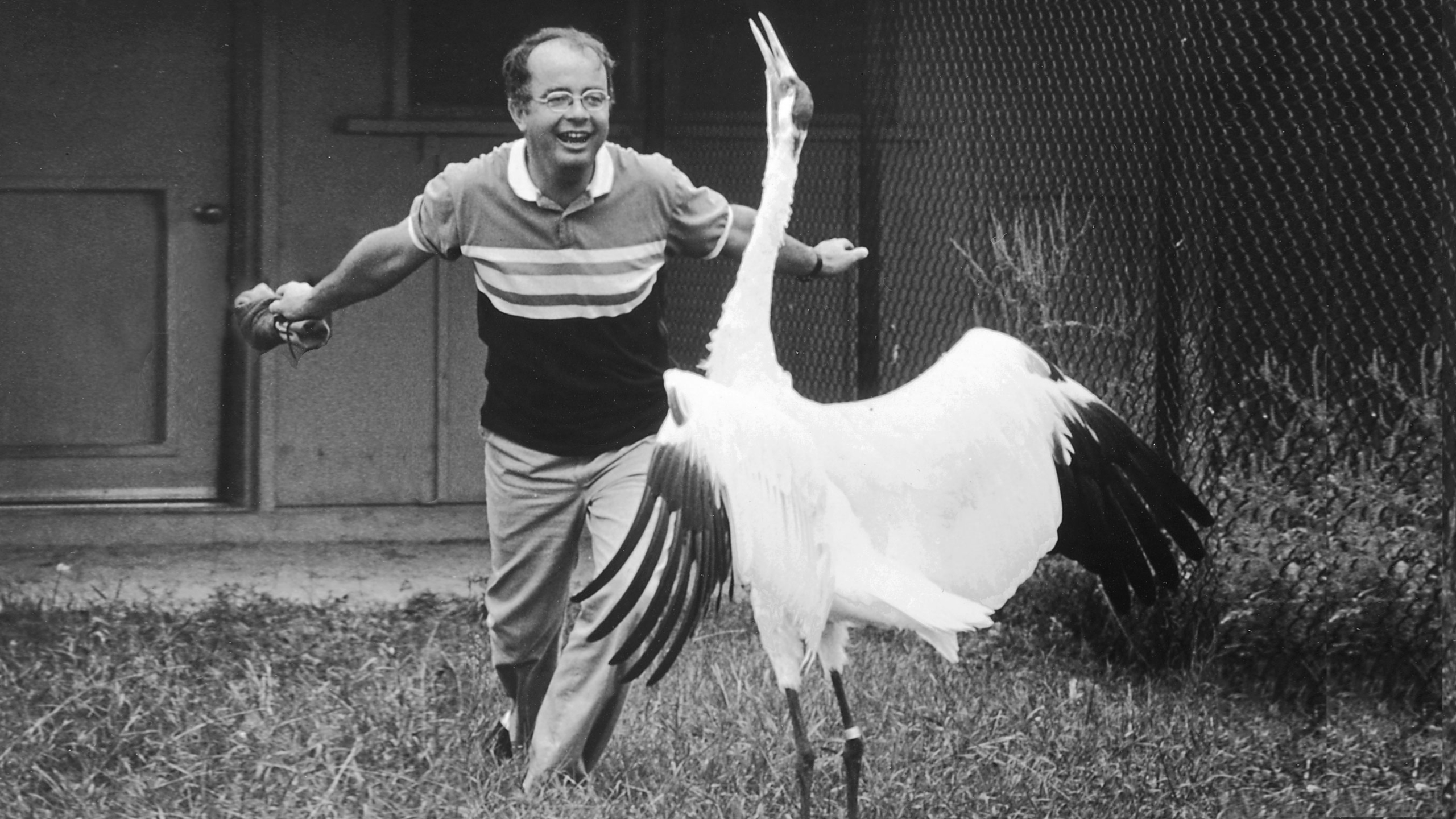

Feeling lucky to be outside when they passed over, I remembered the story behind that distinctive sound—a story which spanned decades of trial and error and included the trials and eventual triumph of a crane-dancing scientist named George Archibald.

Photo Credit: Greg Archibald

In the late 1940s, only twenty-one whooping cranes remained in the wild, and the entire population overwintered at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge on the Texas coast. These magnificent birds have a seven-foot wingspan, mate for life, and if they’re lucky raise just one or two chicks each year. The future survival of the entire species was in jeopardy. What if a strong winter storm were to decimate the entire population, or an oil spill to contaminate the saltwater marsh they depend on? Even though it had been illegal to hunt whooping cranes or gather their eggs for several decades, loss of habitat along their migratory route coupled with hazards like power lines had continued to take a toll. We were in danger of losing North America’s largest bird forever and desperate measures were in order. A captive breeding program helped the situation, but by the winter of 1974-75 there were only forty-nine birds left in the wild, and their situation was precarious.

In 1976, scientists at the San Antonio Zoo hoped that a rescued female whooping crane named Tex would mate and improve the odds for survival of the entire species. The only problem was that Tex had been raised without other whooping cranes and was imprinted on humans. Enter George Archibald, ornithologist and co-founder of the International Crane Foundation. It wasn’t long before Archibald figured out that Tex didn’t get along with other cranes. To get her to lay an egg, George needed to have Tex believe he was her mate, and then they could use artificial insemination to make the egg fertile. Archibald and Tex danced for seven long years before the plan worked, and she finally laid a fertile egg.

The resulting chick was named Gee Whiz and made George Archibald famous. Amid much laughter, Archibald demonstrated his crane-dancing antics for television audiences on The Johnny Carson Show—and also revealed his absolute dedication to saving this species. From those early days of trial and error, scientists have learned not to let crane chicks imprint on humans, and workers at captive breeding facilities use crane costumes when working with young chicks to keep the birds as wild as possible before their release.

Photo Credit: Greg Lavaty

Now as I hear that wild, beautiful call of the whooping crane, I smile and think of that crane-dancing scientist, the years of trial and error, and the eventual triumph that has saved this magnificent bird from extinction.

Find out more about George Archibald and his work with cranes in his book, My Life with Cranes.

Ann Miller was on staff with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department for many years before becoming a certified Interpretive Guide and working as an Interpretive Ranger at Yellowstone National Park. Since joining our Interpretive Insights team, she has assisted with project research and planning using her extensive experience both as a frontline interpreter, and also as a middle school science teacher.